Recently, a colleague asked for help with a citation and I think that the citation allows us to inquire into several interesting aspects of research into older English materials. The cite was: 15 E. 3 Cor. 116

The citation was brought to me as an older English case and before I saw the citation the original librarian with the question had proceeded as if it were a case. He examined the Cardiff Index to Legal Abbreviations. But, the reporters that he was directed to were odd and seemed wrong. It’s not entirely clear what is being cited. Is this one citation? A string cite? If this is taken as a string cite, or two citations that were somehow mangled, then Cardiff indicates that E. might be East’s Term Reports covering the King’s Bench from 1801-1812. Cor. would be Coryton’s Reports from the Indian state of West Bengal, covering cases from 1864-1865. Since the reporters don’t cover the same years, are there two citations here. Or is there something else going on?

It was at this point that I got involved. When I looked at the citation, I saw that the citation had a number of errors, but “E. 3”; was a tip off. Prior to the 1960s, and In the United States, English Statutes are cited in the following form: [regnal year] [monarch’s name and number] [number of the law in that regnal year’s parliament]. “E” isn’t an abbreviation that is used for monarchs, but there have been several kings named Edward (there have been two Elizabeths, so I discounted that possibility), perhaps this was a law from the reign of Edward 3. He was King of England for 51 years, so if he held a parliament in his 15th year, we might be getting somewhere.

The 116 was bothersome because prior to the seventeenth century, there were not that many Acts of Parliament certainly not in a session. Also, if this was from the middle ages, I would expect to see a “statute” reference in the citation. In the middle ages, it was considered that one law was passed in each session of parliament. One will generally find a “st.” or “stat” in the citation to indicate the session of Parliament. That one law was called the “statute” and that what we would consider laws were called “chapters.”

I thought that maybe the 116 came from someone dropping the stat. and pushing the numbers together. If this is a law from Edward 3’s reign, the law could be from 1341 and the more common citation would have been something like 15 Edw. 3 stat. 1 Cap. ??. “stat. 1” means that the law was passed in the first session of parliament during the 15th regnal year of Edward 3’s reign. There were three “statutes” in the 15th year of Edward 3’s reign.

So, I turned to 15 Edw. 3 St. 1 to see how many chapters there were and whether the sixth or sixteenth looked right. 15 Edw. 3 stat. 1 had six chapters. The sixth was entitled “Ministers of the Church shall not answer before the King’s Justices for Things done touching the Jurisdiction of the Church” The cite would be something like 15 Edw. 3 stat. 1, Cap. 6. This could be what he was looking for. Interestingly, 15 Edw. 3 stat. 2 repealed 15 Edw. 3 stat. 1 because it was made without the consent of the King.

Alternatively, the error might be with the “15.” If I go to 14 Edw. 3 stat. 1, Cor. 16, I get

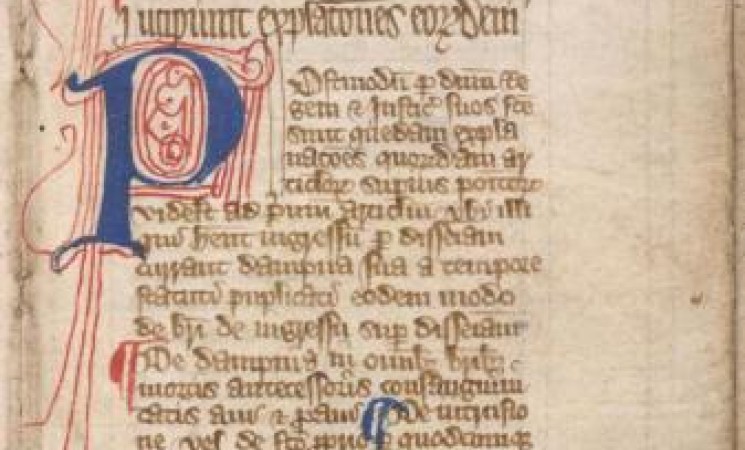

Page xxxv of the Statutes of the Realm has a footnote that discusses the process by which statutes were made and Chapters were assigned in this era

There are a couple of additional complexities that I think are worth mentioning. The first is that the year represented is the regnal year. For Edward 3, the regnal year ran from January 25 through January 24. Since he died on June 21st, Richard II’s regnal year ran from June 22 through June 21. (Interestingly, Richard II was the first king whose regnal year was dated to the day following the death of the prior king). Before Richard, the regnal year started with the next king’s coronation, often leaving gaps of days or weeks between monarchs. There is an excellent Wikipedia page that lists the regnal years for English monarchs. Several provide a list of English (and later) legislation, including one that covers until 1483.

Since the regnal years are fairly arbitrary, Parliaments frequently had sessions that extended from one regnal year to the next. In that case, the statute would be cited as the Statute of Westminster 1931, 22 & 23 Geo. 5 c. 4.

The final question is where did I find the Acts?

If you have access to the English database Justis, it is the easiest tool to find old repealed statutes. The only downside to searching Justis is that they don’t do regnal years. Therefore, you have to guess about which “real” year the law was passed. If I use the “Quick Search” and look for 15 edw 3 st. 1, I get a number of laws one dating to 1978 and I do get the repeal, but I don’t get the actual law. Funnily, the best search is a simple date search for all laws passed between 1339 and 1341. I get 87 sections that I can display by date or relevance and I can conduct searches within them.

Another excellent resource is the Statutes of the Realm. These were put together in the early 19th century and contain all of the laws (that could be found), both those in force and those repealed, that were passed up to 1713. A few volumes are available at the Internet Archive and Google Books, unfortunately volume 1 is not one of them.

So, to find these laws, you need to find a print version of the Statutes of the Realm (it was reprinted recently) or, if you have access to Hein Online, you can find the Statutes of the Realm there

If you aren’t concerned about repealed laws, there are several resources that can be used to find old English laws. One place is legislation.gov.uk. This site is excellent for finding recent legislation. And, while it does have some very old legislation, it doesn’t have it all. Another source are various publications known as “statutes at large.” The volumes of English statutes available at the Internet Archive and Google Books contain only the laws that were in force when the book was printed. None of 15 Edw. 3 was ever in force after the invention of the printing press.