Images of Justice

“Images of Justice” is an exhibit prepared by Seth Quidachay-Swan, who recently completed an internship in the Lillian Goldman Law Library as part of his work toward a Master’s in Library Science from Southern Connecticut State University. Seth will receive his M.L.S. in January 2010, and he also has a J.D. from the University of Minnesota Law School (2008).

In his research for the exhibit, Seth drew on Images of Justice, 96 YALE LAW JOURNAL 1727 (1987), by Judith Resnik and Dennis Curtis of the Yale Law School. This article has evolved into a book that will be out soon: Judith Resnik & Dennis Curtis, Representing Justice: From Renaisance Town Halls to 21st Century Democratic Courtrooms (Yale University Press, forthcoming 2010).

The exhibit is on display on Level L2 of the Law Library, in the wall case to the left of the door to the Paskus-Danziger Rare Book Room.

![]()

IMAGES OF JUSTICE

The image of Justice has been around for over 2000 years. Her lineage traces back to Egypt, Greece and Rome, in depictions of the goddesses Ma’at, Themis, Dike and Justitia. During the medieval period, Justice was adopted by Christian iconography as a representation of ancient virtue. Images of Justice were also common in Renaissance art and texts. Even today, Justice remains recognizable. Her image adorns many modern government buildings and court houses.

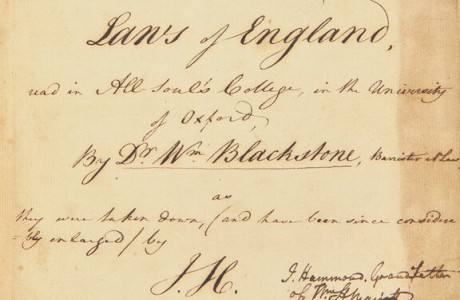

Hugo Grotius, De jure belli ac pacis libri tres (Amsterdam, 1735).

![]()

Today, Justice is most recognizable as a blindfolded woman with a sword and scales. However, earlier depictions of Justice displayed a wide array of allegorical meanings. Justice’s iconic scales measure the strength of a case. Images of a dog and snake with Justice are thought to represent friendship and hatred that could corrupt judgment. Sometimes, Justice’s sword is replaced with a fasces, the Roman symbol of a judge’s power to punish. Two-faced depictions of Justice sought to dispel fears of blind justice morphing into blind fury by prudently leaving one face unblindfolded to carefully wield her sword in meting out judgments and one face blindfolded to show her impartiality in judging the merits of cases.

Joost de Damhoudere, Praxis rerum civilium (Antwerp, 1567).

![]()

Renaissance iconography often depicted Justice with her sister virtues: Prudence (looking into a mirror), Temperance (holding a bridle and water jug), and Fortitude (wearing a lion skin or carrying a broken column). This artistic tradition continued into the 17th and 18th centuries, but is rarely used today.

Hugo Grotius, De jure belli ac pacis libri tres (Frankfurt, 1699).

![]()

Why is Justice so recognizable? Perhaps because Justice represents an idealized model of the legal system, with which political leaders and thinkers throughout history have sought to align themselves. For example, an image of Justice adorns a 1766 edition of Cesare Beccaria’s Dei delitti e delle pene (Of Crimes and Punishments). In this seminal work on criminal justice, Beccaria argued that punishments should be based on the injury caused to society, and that the prevention of crime was more important than its punishment. The text’s portrayal of Justice underscores Beccaria’s argument: Justice turns away from the barbaric and arbitrary punishments of medieval times in favor of a more enlightened penal code.

Cesare Baccaria, Dei delitti e delle pene (Haarlem, 1766).

![]()

– SETH QUIDACHAY-SWAN, Southern Connecticut State University